Super sharp shooter

Led by Joe Poulton, the Columbia Icefield Gigapixel Project (CIGP) is creating a series of ultra-high-resolution images of Western Canada’s Columbia Icefield. Beyond the fun of zooming in on the glaciers and surrounding landscape, the images are helping to enhance local studies of the area, and raising awareness of changes along the Columbia River Basin. Project Pressure caught up with Joe to find out more.

Tell us a little bit about the Columbia Icefield.

The Columbia Icefield rests along the Banff Jasper Highway, aka Icefields Parkway. It is one of two hydrological apexes, the other being Triple Divide Peak in Montana, that provide a source of fresh water for three major watersheds in North America. The watersheds fed by the ice and snow that flow away from the slopes of Snow Dome on the Columbia Icefield include the Columbia, Athabasca and Saskatchewan Rivers. These drain into the Pacific and Arctic oceans, and Hudson Bay.

What’s the aim of your project?

The basic initial stage of the project is to acquire high resolution photographic imagery of all the aspects of the Columbia Icefield from specific locations surrounding and on the Icefield. These high resolution images will provide an additional dataset for Dr. Mike Demuth of the University of Saskatchewan to utilise alongside his Icefield studies. Dr. Demuth and his team have been conducting research on the Icefield for the last three or four years. The more complex part, if all goes well, would be to use this project as a tool for the public along the Columbia River watershed to prepare for the changes that could alter how we use the Columbia River as an economic resource in various segments of commerce.

read more…

Exploring The Alaska Range

Stretched like a crescent moon across nearly seven hundred miles of wilderness, The Alaska Range is a formidable wall of mountains separating the south central coast from the interior of Alaska. Due to its remote location and vast scale, very little of it has been properly documented – which is where Carl Battreall comes in. Combining a passion for photography and the mountains, he is currently working on a large-format book about the range, while conducting research in the more remote sections for Project Pressure partner Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation. We caught up with him to chat all things Alaska.

Tell us a bit about yourself – where did you grow up and where are you based now?

I grew up on the south side of the central Sierra Nevada mountains in California. Both of my parents worked for the Forest Service. I moved to Santa Cruz, California when I was twenty. I worked as a custom Ilfochrome printer, while studying classic, large format, black and white photography with some of the modern masters. In 2001, I moved to Alaska, so I could be near big mountains and glaciers. I am currently living in Anchorage, Alaska with my wife Pam and son Walker.

read more…

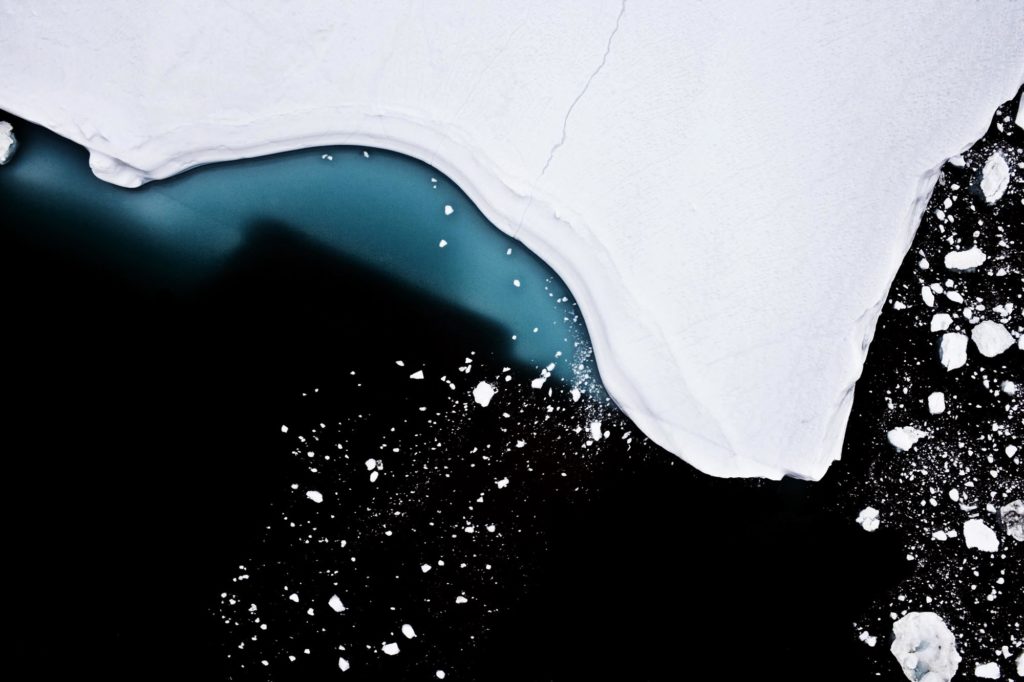

Peter Funch joins Project Pressure

Project Pressure is delighted to welcome photographer Peter Funch as our newest contributing artist – with an expedition to California planned for 2014. Born in Denmark and now based in New York, Peter is perhaps best known for his meticulously constructed street and skyscapes, which show scenes captured and layered over a series of days or even weeks. Following a trip to Greenland during which he captured these stunning images, Project Pressure caught up with him to talk about art, climate change and being cold.

What concepts interest you as an artist?

The idea of people, places or objects in transition related to human and impact; when it has been something and is becoming something new. It can a historic document losing it is value or relevance, a city disappearing – like Detroit – or when glaciers slowly vanish.

What role can art play in a big issue like climate change?

The scientific is one angle, the political is an other, the artistic is third. It is important to have as many angles on a such urgent matter. Different methods and viewpoints can be an eye-opener for another group. it is usually how inventions are made. Olafur Eliasson, Josef Albers, James Turrell and Florian Maier Aichen are, in my eyes, artists who are an interesting place between art and science.

read more…

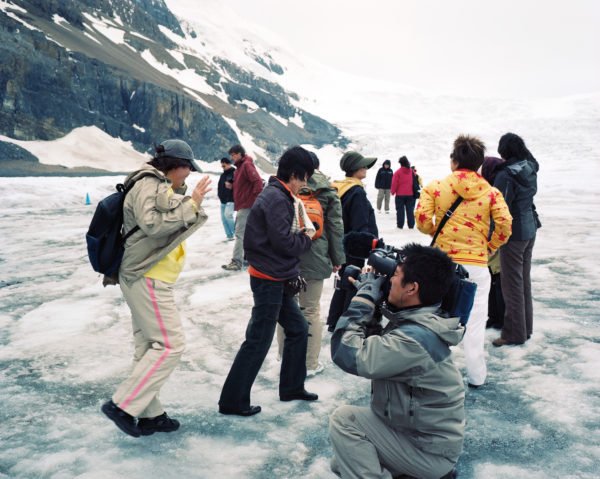

Snapshots from Athabasca

Taking a tongue-in-cheek look at the tourism phenomenon that is Canada’s Athabasca glacier, Andrew Querner captures the surreal juxtaposition of pristine white ice and brightly-attired visitors in his ‘Athabasca’ series. Project Pressure caught up with the Vancouver-based photographer to chat about the glacier and his work…

read more…

Video: Exploring the Pallin glacier tunnel

Working with Stockholm University glaciologist Per Holmlund to identify sites of interest, Project Pressure recently travelled to the far north of Sweden to document glaciers in the Scandinavian Mountains, north of the Arctic Circle. During the expedition, which was supported by Polaroid Eyewear, photographer Klaus Thymann and Project Pressure 50% Director Christopher Seeley undertook an exploration of the Pallin Glacier tunnel, recently uncovered by melting ice.

Adventuring for science

The first results of our collaboration with Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation are now in, with Carl Hancock capturing some superb images like these ones of Snæfellsjökull in Iceland, which Project Pressure originally visited in 2011. Thanks to Carl for taking the time and care to contribute these images and data, and to Gregg and Erin at ASC for setting this up. If you’d like to contribute to Project Pressure, please visit our Get Involved page.

read more…

Inside the Pallin tunnel

Project Pressure recently partnered with Polaroid Sunglasses to mount an expedition to Arctic Sweden. Among other sites, the team had an opportunity to explore the Pallin glacier tunnel. Uncovered by melting ice after being hidden for fifty years, this incredible natural wonder is one of the few glacial tunnels in the world that are safe to access.

A video about the tunnel with some background from glaciologist Per Holmlund is currently showing on The Guardian’s environment page.

Northern exposure

Renowned photographer and commercial fisherman Corey Arnold is currently documenting glaciers in Svalbard for Project Pressure, thanks to a grant from the Lighthouse Foundation. Beyond stunning shots of the ice, he’s also capturing a taste of what life is like for scientists living and working at the Polish research station in Hornsund. We’ll be posting more soon, or check out Instagram for a little preview.

Trading places

Project Pressure’s Chris Seeley and Klaus Thymann during a recent expedition to northern Sweden. It sounds impossible, but in the coming years, the country’s highest point is set to change…

Towering high above the surrounding peaks of the Scandinavian Mountains in northern Sweden, the peak of the Kebnekaise massif currently stands at 2100m – but it won’t be that way for long. Its ice-covered summit is slowly melting, and will shortly lose its place as the country’s highest point.

“One of the glaciers is currently the highest summit in Sweden, but it has changed over time,” explains glaciologist Per Holmlund, who Project Pressure caught up with en route to a recent expedition in the region. “During the last fifty years, the total mass has decreased significantly, so now it’s much more sensitive to warm summers.”

A glaciologist at the University of Stockholm, Holmlund has been studying the area for forty years – contributing to one of the longest-running glacier mass balance studies on earth. He and his team have produced a rich record of historical images and also the most up-to-date maps available, both of which Project Pressure used to plan the expedition.

Located inside the Arctic Circle, Kebnekaise has two peaks: the glaciated southern peak which currently stands as the nation’s highest point, and a rocky northern summit. The southern peak’s place in the record books was once a little more assured. Rising to 2125m feet in historical records, it easily beat its 2097m little brother to the title. Now, though, with changes to the glacier’s mass, the icy crown of Sweden is slowly sinking.

“In the beginning of the 20th century we believed that it was up to something like 2125m but then it started to decrease in elevation. By mid-century it was around 2120m and during the last forty years it has been undulating with a frequency of about ten years. Now, during the 21st century, it has dropped down another ten metres. It’s a very obvious decreasing trend.”

As Holmlund points out, the rock beneath the glacier only reaches up to 2060m, so if it becomes completely ice-free it will actually be demoted to the fourth highest peak in the country. Beyond just an interesting footnote for the record books, Sweden’s melting mountain stands as powerful symbol of the way the planet is changing.

“It’s very difficult to tell exactly when the change will occur,” concludes Holmlund, “but over the last ten years or so the decreasing trend has been in the order of a half metre per year. If we have some snow-rich winters and cold summers it will delay the changeover, but within ten years it’s likely to happen.”

Image: Project Pressure’s recent expedition to Sweden

Adventures in science

Project Pressure’s collaboration with Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation is continuing apace, with adventurer Carl Hancock visiting Snæfellsjökull and other glaciers in Iceland for us recently. Later this year, adventuring aid worker Ricky Munday will be travelling to South America to climb the three highest peaks on the continent and conduct some science along the way. We caught up with him to learn more…

Project Pressure: What are your expedition’s objectives?

Ricky Munday: This 38-day expedition is the latest leg in my long-term project to climb the 3 highest mountains on every continent – the Triple 7 Summits. This has never been completed. Along the way, we’ll be supporting ongoing scientific research on South America’s receding glaciers by collecting rock & ice samples for later analysis by world-class researchers, and creating a geo-tagged photographic record of glaciers for you guys. We’re also planning to raise a substantial sum of money to support cancer victims in the UK.

What kind of training are you doing?

I visited Scotland in April with one of the other team members to get some training in on the West Highland Way. We completed the 155km in 5 days, and were lucky to get fantastic weather – you can see some photos from that training here. We have just completed some training in Venezuela and in August we will climb Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe (Russia – 5,642m). The range of climates and ecosystems that we will visit over the course of the next seven months are incredible; from the rain-soaked forests and ancient rock formations of the Guiana Shield; to the glaciated peaks of the Caucasus Mountains; and finally to the dry deserts of the Altiplano.

What has been your best previous experience in the mountains previously?

My best experience in the mountains is always my last – in this case spending two days on the summit plateau of Roraima in the Gran Sabana of Venezuela (pictured below). We trekked to the Proa in the Guyana sector but unfortunately, it was cloudy and there were no views. It was deeply disappointing after three hard days’ trekking. As we were trekking back to our cave camp, the local guide noticed the cloud cover shifting. For just a few minutes we were treated to an awesome site over the rainforests of Guyana. Breathing fresh mountain air in a remote mountain range; watching the sun rise or set at a high elevation where few people have been; witnessing a cloud inversion over a Scottish glen – these are the experiences that touch my soul.

Why you think its important to contribute to science?

I believe that we all have a responsibility to contribute to a better understanding of our planet. In my case, becaue I have the privilege of visiting places that many people can only dream of, I feel compelled to support researchers who would other wise have no access to samples or data from those remote areas. Although I am a Chartered Accountant, my background is science: I originally studied Zoology and dreamed of being a field researcher. My job now is focused on supporting the most vulnerable people, but my own passion is understanding and protecting our planet.

We’ll keep you posted on Ricky’s expedition, and you can sponsor him via JustGiving and contribute to Project Pressure here.